There was a period of time when I took a series of photos in front of dumpsters and trash cans with the express purpose of using them as dating profile pictures. I imagined that I would have overheard-on-Bumble-type conversations with prospective matches that would go something like this:

Match: Why are all your photos in front of dumpsters?

Me: Because life is sometimes trash!

Match: Why do you feel that way?

My: My husband died not too long ago.

In this fantasy scenario, my match would then reply in a compassionate and thoughtful way and we would begin a deep and respectful conversation.

Spoiler alert: This did not happen.

Soon enough, I felt that it would be easier to be upfront about my widowed status instead of hoping that it would naturally come up in conversation. I put it in my bio, which read something like, “I’m recently widowed and trying to figure out what’s next.”

Deciding how much of your past to reveal to another person can be difficult, especially when the past experience is a notably heavy one. For me, I decided transparency was best when it came to dating. At the same time, I’ve met other young widows who waited until a few dates in to drop the news about their dead spouse.

There’s no right or wrong way to divulge this kind of information, just as there’s no way to know how the other person will react. There’s also no need to have one set approach—sometimes, you may want to reveal your past to someone new; other times, you might prefer to keep your history to yourself.

In How to Lose Everything, Christa Couture writes about the mental gymnastics she performed when asked if she had children. Her son, Emmett, lived just one day. Couture’s second child, Ford, died at 14 months old.

Each time I was asked, I twitched or winced, still unprepared for it. And each time, I made a decision on how to answer, trying to gauge what the subsequent options would be, how the person I was talking to might respond. I was usually making a quick judgment call on someone I barely knew, guessing what their spiritual leaning might be, their openness to sorrow, where they landed on the hug-it-out to suck-it-up spectrum. Whether saying “yes” seemed like the right or wrong choice depended on how my own beliefs, openness, and axis aligned or collided with theirs.

Today, Couture has a daughter, Sona, who is 4. Her answer about whether she has kids is a bit tidier, but keeping Emmett and Ford’s memories alive still matters to her. Even all these years later—her boys would now be 15 and 12—she still falters when asked about her children. Sometimes, she chooses to talk about her sons. Other times, she keeps them to herself.

I’m writing about this topic because a reader suggested it. Her son died in January 2020, when he was nearly 10 months old. Today, she finds herself facing the same awkwardness that Couture detailed. “When do you tell someone about the loss you experienced and the grief you’re navigating?” she asked.

It’s a good question. After Jamie died, I was on edge whenever I’d meet new people. More often than not, I’d try to keep my grief hidden—despite the fact that, in those early months, it was all I wanted to talk about. I feared making strangers uncomfortable, reminding them of their own mortality, and bringing conversations to a halt. I felt like the walking version of a record scratch.

And so, more often than not, I would hide my truth. My grief didn’t seem to fit into a society where the expected answer to “How are you?” is a cheery “Good!” or “Can’t complain!”

Sometimes, though, my relationship status would come up. Someone would ask if I was married or had kids. Like Couture so aptly described, I’d have to do some quick thinking. Should I respond with a simple “no,” or tell the full story? Is this an appropriate time to be vulnerable? How will my answer make them feel? How might they respond? It was a fraught guessing game.

For a month straight, I wore black clothing every day after Jamie’s funeral as a way to match my mood. Ultimately, that wardrobe choice was hard to keep up with, especially in steamy Florida. I remember wishing that it was still commonplace to wear black armbands, or that there was another way to signal I was in mourning. I wanted a simple, socially acceptable way to broadcast to others that I was sad, that my mind and heart were someplace else entirely.

I think that’s why my dating dumpster photos felt so liberating. I loved having control over the narrative—telling people how I really felt. I could share my widowed status on my terms, in my own tongue-in-cheek way. It’s also why I fell in love with writing about grief. I was tired of hiding my story because it made some people uncomfortable.

For a long time, I felt like being a widow was my main identity. And while that’s no longer the case, losing Jamie still plays a major role in my life and always will. His death shaped the person I am today and how I see the world. It affects the choices I make, the risks I take, and the depth with which I love.

At some point, I decided to stop worrying about how other people might respond to the fact that my husband died so young. Instead of questioning whether someone might feel awkward, I learned how to honor my own feelings. Do I want to talk about Jamie today? Will it make me feel lighter to share my grief? Do I trust this person and this situation?

Life is sometimes trash. It’s not up to me to protect other people from that fact. If someone winces or changes the conversation after I bring up a difficult subject, that’s on them. It says more about their life experience and view of the world than it does about me.

Thankfully, life can also be surprising and wonderful. Sometimes, choosing to open up about your difficult past can make for a beautiful connection in the present. Being open about my grief helped me meet my partner, Billy. It’s connected me with all of you—readers who have been generous in sharing their own difficult stories. It also led to several small but meaningful interactions with strangers. There was my seatmate on a plane trip who talked about the fragility of life; the woman in a New Orleans jazz club bathroom stall who cried about her divorce as I cried about Jamie’s death (we both might have been a little tipsy, but hey, it was still a special experience); and I’ll never forget the person I sat next to at a professional dinner who told me about losing her husband many years ago. “I haven’t talked about this in a long time,” she said.

In the end, there’s no right or wrong way to share your sorrow. It’s your story and your choice.

xoxo

KHG

p.s. One of the risks of opening up to others about a painful subject is getting a tone-deaf reply in response. (Pro-tip: Any response that starts with “At least ...” is probably not helpful!) What are some of the cringeworthy responses you’ve gotten in response to a difficult topic? I would love to hear your stories and compile a list. Let’s learn what not to say together!

Reply to this email, leave a comment, or send me a message. I’ll feature a variety of replies in Friday’s subscriber-only newsletter.

💖 Sharing is caring

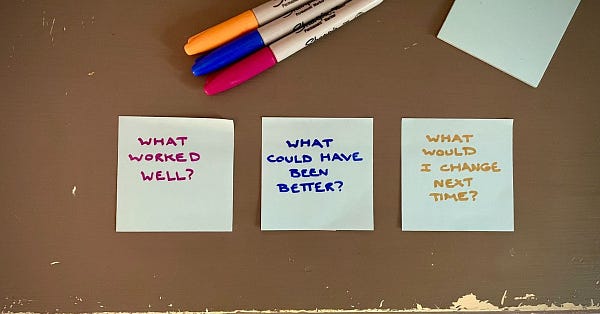

Well thanks, Erica! I think you’re pretty brilliant, too. In case you missed Friday’s subscriber-only newsletter, several readers shared their responses to the post-mortem framework. As one person commented, “I loved reading the feedback in this one!”

Word of mouth goes a long way in the newsletter world! Sharing, recommending, and forwarding this newsletter all helps.

👋 Hello there

There are quite a few new readers here. Hello, friends! Welcome to My Sweet Dumb Brain.

If you’re new, I set a goal this year to reach 5,000 people on my email list and 500 paying subscribers by the end of 2021. As of today, I’m at 5,150 readers (wow!) and 463 subscribers.

Will you help me meet my subscriber goal? It’s just $5/month or $35/year. Thank you!

My Sweet Dumb Brain is written by Katie Hawkins-Gaar. It’s edited by Rebecca Coates, who can be a bit of an over-sharer at times and worries about talking ~too much~ about her Dad’s passing.

This newsletter contains a Bookshop.org affiliate link.

This is one my favorite of your pieces Katie. It's tender & funny AND contains really good, practical advice for the grieving. Love it. xx

First off, you look beautiful in all your 'trash can photos'!!

My daughter, age 40 died unexpectantly just 14 months ago. When I meet new people and they ask how many children I have, I always include my daughter. Sometimes I feel guilty not telling them 'the truth' that she's gone. Sometimes I go into great lengths to describe her as if she's still alive. Either way I feel awkward and sad. Am I protecting othe? I'm still strugggling with this.