We should be feeling sad. Here’s how grief can guide us.

Take that sadness and transform it into action.

I carefully considered what to write in today’s newsletter—looking for ways to add value to the conversation around racism in America without making it about myself, or taking away from someone else’s perspective. Although I don’t have newsletter demographic data, I’m assuming that My Sweet Dumb Brain reaches a largely white audience. I wrote this essay with those readers in mind; I hope it’s helpful.

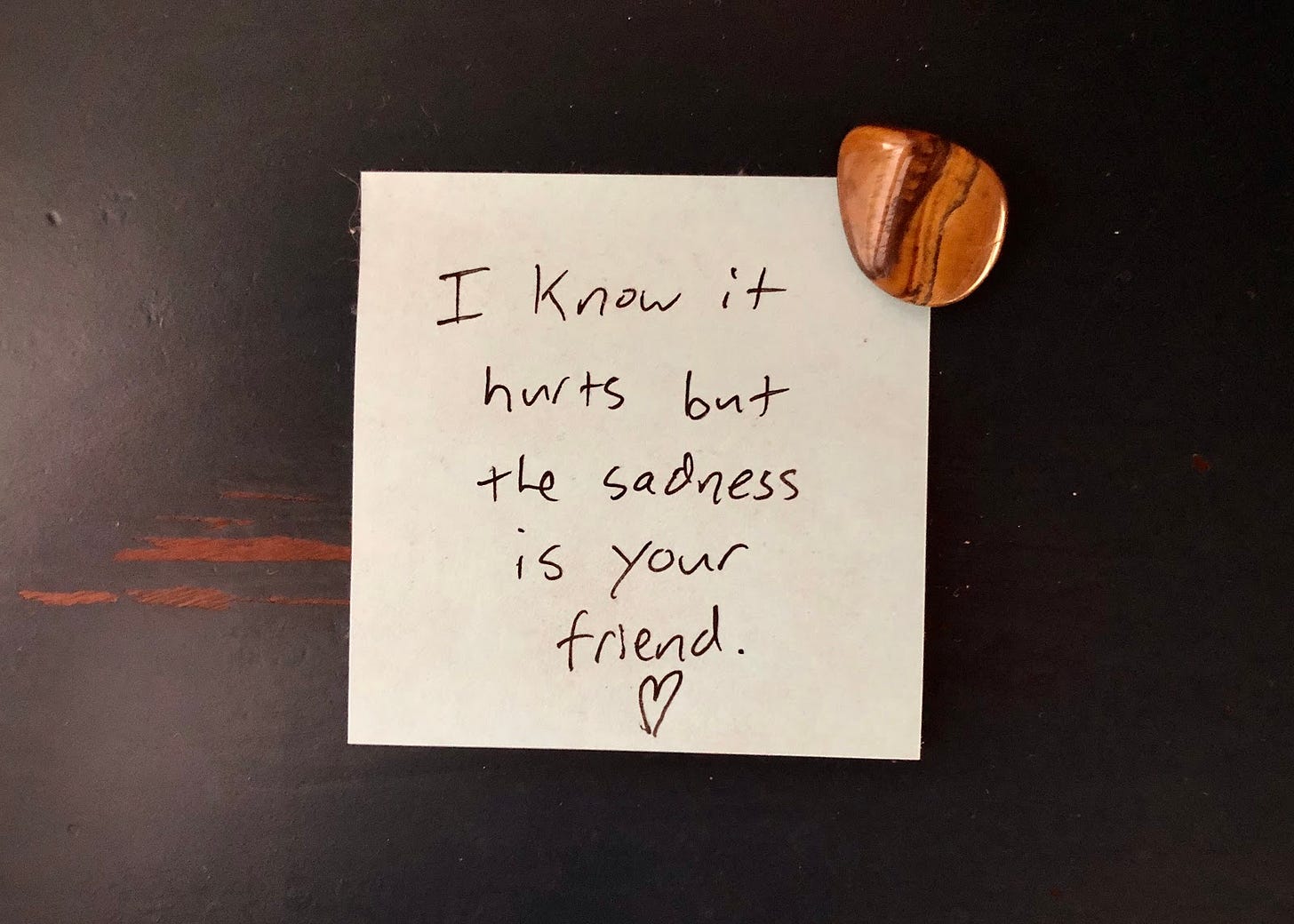

Last February, on the two-year anniversary of my husband’s death, my partner Billy placed a Post-It note on my laptop. The days leading up to that milestone had been miserable—full of tears and anger, guilt and frustration, sorrow and pain.

Billy’s note was simple and to the point: “I know it hurts, but the sadness is your friend.” I’ve kept it ever since. That light blue square now sits on my dresser, right next to my late husband’s urn. It’s a welcome reminder whenever I’m having a particularly hard day.

Like many of you, I have been feeling a deep sense of sadness lately. Still, I don’t know what it’s like to be Black in America. I don’t know what it’s like to see people who look like me be routinely targeted and murdered by the police. I can’t even pretend to fully understand the extent of systemic racism in our country, though I am doing my best to learn.

I do know what it’s like to be white in America, and to live with endless amounts of privilege. I know what it’s like to witness the events of the past few weeks—and to reflect on the racism I’ve witnessed my entire life—and then look more deeply at myself, my beliefs, and my actions.

I also know that what I’m feeling right now, and what so many of us are experiencing, is grief.

That’s why I’ve been thinking about that Post-It note. It’s something I needed to hear back then, and it’s a reminder I need now:

I know it hurts, but the sadness is your friend.

We are in the midst of a mass reckoning. We are awakening to the depths of racial injustice in America, while also facing a pandemic that has killed more than 400,000 people worldwide. We should be feeling awful. We should be feeling angry. We should be cycling through the stages of grief, like bargaining and depression, denial and acceptance.

“Miserable is exactly how the white people who want to help should be feeling right now,” Rebecca Carroll writes in The Atlantic. “They should sit with that misery until something breaks in their brain, the narrative changes in their psyche, and the legacy of emotional paralysis lifts entirely.”

Contrary to how it feels, the discomfort we are experiencing is a very good thing. The fact that so many of us are unable to shake our sorrow and look away is a sign of progress. The anger we are feeling is fuel for a fight that we should have been fighting seriously a long time ago.

Thankfully, grief can teach us in this moment. If we accept the fact that we’re grieving, we can better identify what we’re feeling, and why we might act a certain way. Owning and understanding grief is empowering. It allows us to move forward.

If you examine the stages of grief, it’s easy to see how they relate to both crises we’re confronting.

First, there’s denial. It’s tempting to tell ourselves that the situation isn’t actually that bad, or that it doesn’t exist. We try to continue to live our lives how we always have, for as long as we can. When it comes to acknowledging racial injustice, many of us have lived in this stage for far too long.

Next, there’s anger. We’re seeing a lot of anger these days. There were the people angrily protesting coronavirus lockdowns, and there are now people angrily protesting police brutality—two very different groups, but factions expressing the same emotion. Even if we’re not in the streets, we are likely feeling angry. How the hell did we get here? When will it get better?

Chances are we’ve done some bargaining with ourselves. Bargaining can look like the decision not to wear a face mask just this once, despite knowing the latest guidance from health officials. Bargaining can also look like going through the motions of allyship in hopes of returning to status-quo. If I share this list of anti-racism resources, can I go back to caring about other things?

None of the stages of grief are fun. Depression is an especially tough one. When you’re here, you can easily feel hopeless. You lose sight of what’s ahead. You have no choice but to face your own shortcomings. Because this stage is so uncomfortable, many of us abandon it. We retreat to an earlier stage that feels more familiar, like anger or denial.

Eventually—after a lot of sadness and pain, missteps and mistakes, and hard emotional work—we reach acceptance. Acceptance doesn’t mean we say, Oh, I guess I’m ok with this thing I’m mourning! It means we accept that that thing is real (such as coronavirus, systemic racism, or the death of a loved one), and that it’s something we will always mourn. This stage is about making peace with the pain, and being able to move forward alongside it.

And then there’s the sixth stage, which was added to the grief framework in 2019: Meaning.

I think we’re a long way off from finding true meaning in what we are experiencing in the United States today. There have been glimmers of hope and encouragement over the past few weeks, but there’s far more pain to reckon with in the coming weeks, months, and years as we navigate the collective trauma we've endured and begin to heal as a nation. We can’t rush ahead to this final feel-good stage. First, we have to sit with our discomfort. We have to feel anger and depression, and use those feelings for good. We have to befriend the sadness that’s hanging over us. We have work to do.

In Joan Didion’s memoir about her husband’s death, The Year of Magical Thinking, she writes, “We are not idealized wild things. We are imperfect mortal beings, aware of that mortality even as we push it away, failed by our very complication, so wired that when we mourn our losses we also mourn, for better or for worse, ourselves. As we were. As we are no longer. As we will one day not be at all.”

This, my friends, is why we feel so bad. It is human to experience loss and to feel sorry for ourselves. It’s not the noblest of human traits, but it happens. And right now, loss is inescapable. We are mourning the lives of Black people like George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor. We are mourning the hundreds of thousands of lives lost to a pandemic that rages on. We are mourning the routines we once knew, the safety we once felt, and the beliefs that we were taught and now have to contend with. We are mourning so much; it’s impossible not to mourn ourselves along the way.

But all is not lost. I firmly believe that as long as we’re aware of this tendency—as long as we don’t ignore our feelings, or use them as an excuse to act out—then we can work with it. By using tools like the stages of grief framework, we can better understand what we’re feeling, and why we are tempted to act in a certain way. By better understanding and owning our grief, we can transform our sadness into action. We can stand alongside those whose losses are greater than ours. We can use our grief for good.

xoxo,

KHG

What can grief teach us in this moment?

The more I’ve grappled with grief, the more I realized how common it is. It’s human and healthy to grieve. It makes all the sense in the world that we’re feeling collective grief right now.

That’s why I appreciate the grief stages. It’s useful to have a shared framework to help explain the things we might be feeling, and thoughts we might be having.

I’d love to hear your thoughts in response to today’s essay. Are you working through a particular stage of grief right now? If so, what are you learning from it? Do the stages of grief help illustrate what you’re experiencing, or what you see others going through? Or perhaps you don’t believe in the stages of grief, and having a tidy explanation for a messy experience—that’s valid, too.

Share your thoughts, perspectives, and stories by replying to this email, leaving a comment, or sending me a message. I’ll compile your replies in Thursday’s subscriber-only email, crediting you by first name only (let me know if you’d like to remain anonymous).

If you’re not a paying subscriber, you can still contribute your wisdom. If I use your response, I’ll be sure to forward along Thursday’s newsletter so you can read it. And it’s never too late to become a paying subscriber!

My Sweet Dumb Brain is written by Katie Hawkins-Gaar. It’s edited by Rebecca Coates, who’s mourning a lot these days, and learning to ride those grief waves like a champion—even if it doesn’t always feel that way.

Creo que en este tiempo todos hemos experimentado emociones muy fuertes. De dolor de pérdida, de impotencia de frustración. Me duelen las muertes en cualquier circunstancia, aquellas impredecibles por la pandemia que ocurren todos los días de manera incontrolable. Aquellas de los seres que amas, que te tocan cuando llega el momento. Pero creo no hay peor dolor que aquellas que están relacionadas con el racismo, la desaparición forzada de personas o las producto de feminicidios. Esas me duelen porque no alcanzo a entender la deformación, la insensibilidad y la miseria humana.

I am feeling so full of emotions and they all feel so big right now.

But I think I am mostly feeling angry:

Angry at the injustice.

Angry that the world is having what I feel are the same race discussions as before I was born.

Angry at leadership in this country.

Angry at my white fore fathers, my own father... at how they think and how their thinking influenced my upbringing.

Angry at being white.

Angry at my guilt and how is plunges me into denial and makes me feel stuck.

Angry at rioters.

Angry at police.

Angry at All Lives Matter:

Angry that I feel sad and useless in such a big Important movement.

After all the anger I feel wiped out and sad. Desperate for meaning to emerge from this all.