I was well into my 20s when I finally figured out that I was an introvert. I knew that I loved to read and write, needed time to formulate my thoughts, preferred deep conversations with a friend to small talk with a group, and relished cozy nights alone. I didn’t know that those things meant that I was introverted. I thought they meant I didn’t quite fit in.

At the time, I was newly married to Jamie—one of the most extroverted people I’ve ever known. Jamie adored a crowd. He loved being on stage, telling jokes, laughing loudly, and meeting new people. He befriended seemingly everyone he met. (Years ago, the salesclerk at our grocery cheese counter cried when Jamie announced that we were moving to Florida. Seriously, he was friends with everyone! Even the cheese counter dude.) I was envious of Jamie’s gregariousness and would always ask him for tips. Why can’t I be more outgoing? I’d lament.

The place where I struggled most with this was work. At CNN, where I climbed from intern to producer to, eventually, the head of a department, I felt like the odd person out. I was a quiet worker, someone who preferred to collaborate one-on-one instead of in big groups. I’d be slow to speak up in meetings, needing time first to collect my thoughts. I’d whisper jokes to the person next to me, rather than commanding the attention of the room.

I was the opposite of the outspoken, fast-talking, well-connected type that seemed to excel within the organization. Despite positive reviews from my bosses and direct reports, there were many times that I believed I wasn’t good at my job—simply because I wasn’t loud or didn’t put myself out there enough.

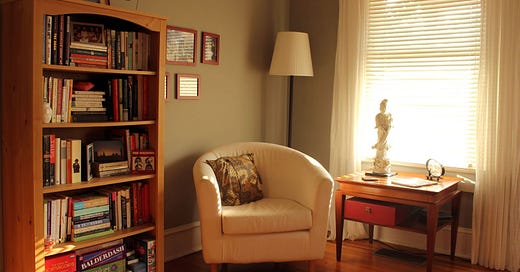

It’s not that I hated being around people or even in front of a crowd. Jamie and I hosted plenty of big parties, and—after lots of practice and training—I eventually grew to enjoy public speaking. I had plenty of friends, went to concerts and clubs, and looked forward to nights out. But before too long, those things would exhaust me. I’d crave time alone, just me and my thoughts, and perhaps a really good book.

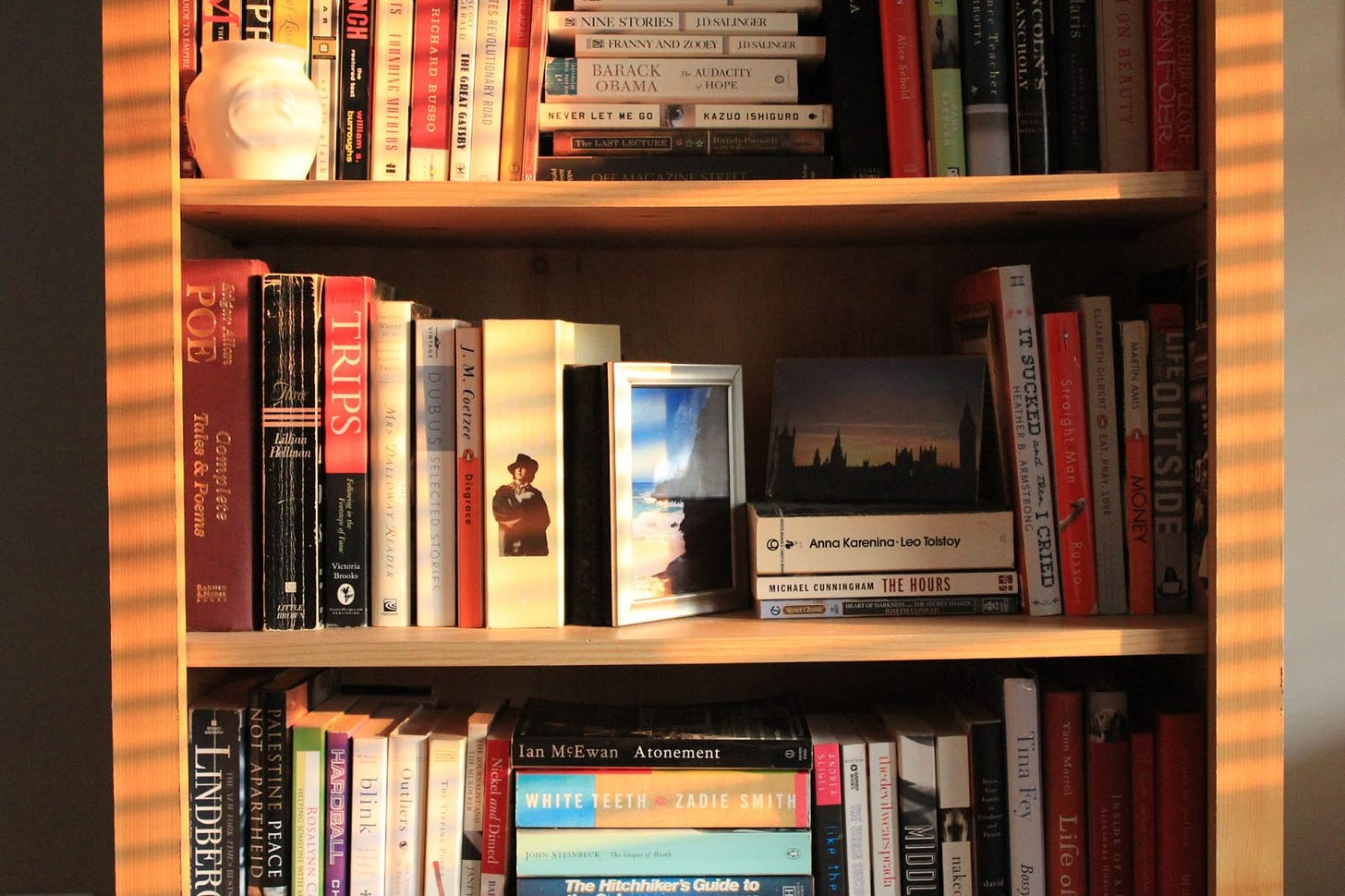

One of those books was Susan Cain’s Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking. It helped me to better understand and accept my introverted tendencies—and see myself as the leader that I never thought I could be. In her bestseller, just like her wildly popular TED Talk, Cain argues that Western culture undervalues introverts, and that we lose a lot by doing so. She explains that introverts aren’t reclusive, shy, or slow—more often than not, they’re simply misunderstood.

Since Cain’s book came out in 2012, the general population’s understanding of introversion and extroversion has grown—and many introverts, like me, have learned how to embrace their personality type. We know that extroverts gain energy by socializing and that introverts recharge by spending time alone. Extroverts are drawn to the outer world of people and activities whereas introverts retreat to the inner world of thoughts and feelings. And extroverts enjoy collaborating in groups and talking things out, while introverts prefer working independently and taking time to formulate their ideas.

Neither of these categories is good or bad—though sometimes society makes it feel that way. Like most things in life, introversion and extroversion exist on a spectrum. Carl Jung, who introduced the terms in his 1921 book Psychological Types, famously said that, “There is no such thing as a pure introvert or extrovert. Such a man would be in the lunatic asylum.”

Some psychologists like Adam Grant claim that the vast majority of people are ambiverts—with both introverted and extroverted tendencies. In a 2013 study, Grant discovered that two-thirds of people have a balance of introverted and extroverted personality traits. The direction that ambiverts lean toward, he said, varies greatly—depending on the situation.

Our pre-pandemic world forced many of us to lean toward extroversion. In Quiet, Cain explains that our most important institutions, schools and workplaces, are designed for extroverts. Classroom desks are often arranged in pods and most offices are open-concept, divided only by low cubicles. In both environments, groupthink, gregariousness, and enthusiasm are prized. Because of this, people who prefer introversion may pretend to be more extroverted in order to succeed.

“Some fool even themselves,” wrote Cain, “until some life event—a layoff, an empty nest, an inheritance that frees them to spend time as they like—jolts them into taking stock of their true natures.”

If I had any doubt whether I was an introvert, the pandemic made it entirely clear. I’ve delighted in long phone calls and weekly Zoom chats with friends, both from the coziness and comfort of my home. I’ve devoured books and caught up on excellent television and movies. I’ve enjoyed quiet dinners at home and idea-generating walks around the neighborhood. Whereas some people are struggling creatively, I’ve been producing some of my best work.

Most of all, I’ve loved not feeling ashamed of my tendencies. It’s currently a badge of honor—an act of greater good—to stay at home, instead of a disappointing choice. I don’t have to feel guilty about turning down an invitation or wanting some alone time, like I have in the past.

In Quiet, Cain writes:

Introversion—along with its cousins sensitivity, seriousness, and shyness—is now a second-class personality trait, somewhere between a disappointment and a pathology. Introverts living under the Extrovert Ideal are like women in a man’s world, discounted because of a trait that goes to the core of who they are. Extroversion is an enormously appealing personality style, but we’ve turned it into an oppressive standard to which most of us feel we must conform.

This, Cain explains, is why many introverts hide their true nature. But over the past year, we haven’t had to do that. We’ve had full permission to be the homebodies we are.

Of course, pandemic life hasn’t been a rosy experience for anyone, whether you’re extroverted, introverted, or somewhere in between. In fact, evidence suggests that introverts have had a tougher time during the pandemic, reporting higher levels of loneliness and unhappiness. No matter how introverted we may be, we all need social interaction—a fact that’s more obvious now than ever. The people who have found creative ways to keep in touch with loved ones have fared best during this socially distant time.

To be clear, I’m not an antisocial curmudgeon. I’m far from that. I desperately miss people. I miss hugs. I miss the din of a busy restaurant and the warmth of a bustling crowd. And yet, once more and more of us are vaccinated and start socializing more regularly, I have no doubt that I will miss this period of quiet, too.

One of the things I hope to take away from pandemic life is not only to stop hiding my introverted side, but to indulge my extroverted tendencies as well. Life is too short—and my emotional battery gets drained too quickly—to not embrace who I am. I want to stop feeling guilty if I need to turn down an invitation or would prefer to be alone. On the other hand, life is also too short to not spend time with the people I love. I also want to get out more and shed some of the social anxiety I’ve carried around for so long.

This kind of harmony is, ultimately, what Cain advocates for at the end of her TED talk. “What I'm saying is that, culturally, we need a much better balance,” she said. “We need more of a yin and yang between these two types.” Cain explained that this is especially critical when it comes to creativity and productivity. “When psychologists look at the lives of the most creative people, what they find are people who are very good at exchanging ideas and advancing ideas, but who also have a serious streak of introversion in them.”

Solitude is crucial to creativity and deep thinking. Socializing is crucial to spreading those gifts. Finding a balance between the two—opportunities for us to connect and to recharge—is the approach I hope our workplaces and schools will take in this pivotal moment of reopening.

In the meantime, I’ll start with myself. As I prepare to reemerge from homebody life, I’ll be taking stock of my introverted and extroverted desires. It’s a good time to indulge my inner ambivert.

xoxo

KHG

p.s. How has the past year altered your personality? Have you become more introverted, or is your extroverted side bursting at the seams? Or maybe you’ve changed in different ways—perhaps you’ve uncovered artistic talents or discovered that you’re a dog person, after all. Do tell! Reply to this email, leave a comment, or send me a message. I’ll round up your replies in Friday’s subscriber-only newsletter.

Sharing is caring

My Sweet Dumb Brain has gone international! Big thanks to Danielle Webb for the lovely shoutout in her Globe and Mail story about reimagining work.

If you’ve been here for a while you know that I’m on a quest to reach 5,000 readers and 500 paying subscribers this year. We are inching ever closer to that goal, and I couldn’t be more excited about it! As of this week, My Sweet Dumb Brain has 4,802 readers and 386 subscribers.

For the next two weeks, I’m offering 25% off subscriptions to My Sweet Dumb Brain. That means you’ll pay $26.25/year or $3.75/month. Paying subscribers receive two newsletters a week, a Tuesday issue like this one, and an exclusive follow-up Friday issue (here’s an example). Not only do you join a thoughtful community and receive valuable insights, you also help support me and my writing career. Win-win!

This offer is good through Tuesday, April 27, which just so happens to be my birthday. If you’ve been wondering what would make a good gift, wonder no more!

My Sweet Dumb Brain is written by Katie Hawkins-Gaar, who, according to the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, is an INFJ. It’s edited by Rebecca Coates, an INFP, whose Facebook profile tagline reads, “I’m incredibly extroverted for an introvert.” (She’s apparently an ambivert, after all!)

This newsletter contains Bookshop.org affiliate links.

I love this one, Katie. (I mean, I love all of them, but this one really resonated with me.)