Today’s newsletter, like many past issues, is something I needed to read—a very basic reminder for my sweet dumb brain.

This is a phase.

I don’t mean this in a dismissive or judgmental way. I’m saying it gently, with good intention. This period is a phase. It will pass. Before I know it, I will be in an entirely different phase, contending with whatever that moment brings, good or bad.

For me, the phase I’m in is one of sleepless nights (hello, 10-month-old sleep regression), a rough patch with my partner (hello, effects of 10-month sleep regression), irritability, a lack of creativity, and anxiety that’s become so commonplace it seems natural.

All of these things will pass. Everything does. But I don’t always remember this. Sometimes, like now, when I’m sleep deprived, grumpy, hormonal, uninspired, and anxious, I convince myself that things will always feel this shitty. That life kinda sucks and that I’m stuck in the suckiness.

And that’s why I’m writing this essay. I need to remember that what I’m going through is a phase and that, sooner or later, things will feel brighter.

I feel a little sheepish writing this—admitting that I’m struggling with such relatively small inconveniences. After all, there are much, much more serious problems happening in the world. Afghanistan is imploding. Louisiana is reeling from Hurricane Ida. And COVID-19 continues to cause deaths and major disruptions around the world. I bet anyone dealing directly with any of those disasters would be thrilled to trade their nightmare experience for one of my sleepless nights.

But these are also things that will pass. These crises are undoubtedly far more serious, with much bigger consequences, but they, too, are temporary. We will not always live in a world where Afghanistan is under siege, where the Gulf Coast is under water, where a virus is unstoppable. Some of these situations will get better. Some, unfortunately, will get worse before they eventually improve. What’s certain is that this period is also a phase. It will not last forever.

This, of course, can be hard to remember—especially when we are in yet another wave of the pandemic, when New Orleans has been hit yet again by a massive hurricane, when Afghanistan is falling apart just as a 20-year war is ending. If you stay glued to the news or social media, it can be easy to convince yourself that things have been and will always be this way.

In an article titled, “What to Do When the Future Feels Hopeless,” The Atlantic’s Arthur C. Brooks offers some helpful advice for this challenging time:

Your future is brighter than what you may think at your darkest moments, so dispute your pessimism not with mindless optimism, but with facts. Build a solid case for something other than the worst-case scenario, and argue it to yourself like a lawyer. And while you’re at it, read fewer stories about the pandemic. You probably aren’t learning anything new, but, rather, just trying to get a bit more certainty about the future, which is impossible.

This is a phase. We will never know what the future holds, but it is an indisputable fact that it won’t be like this forever.

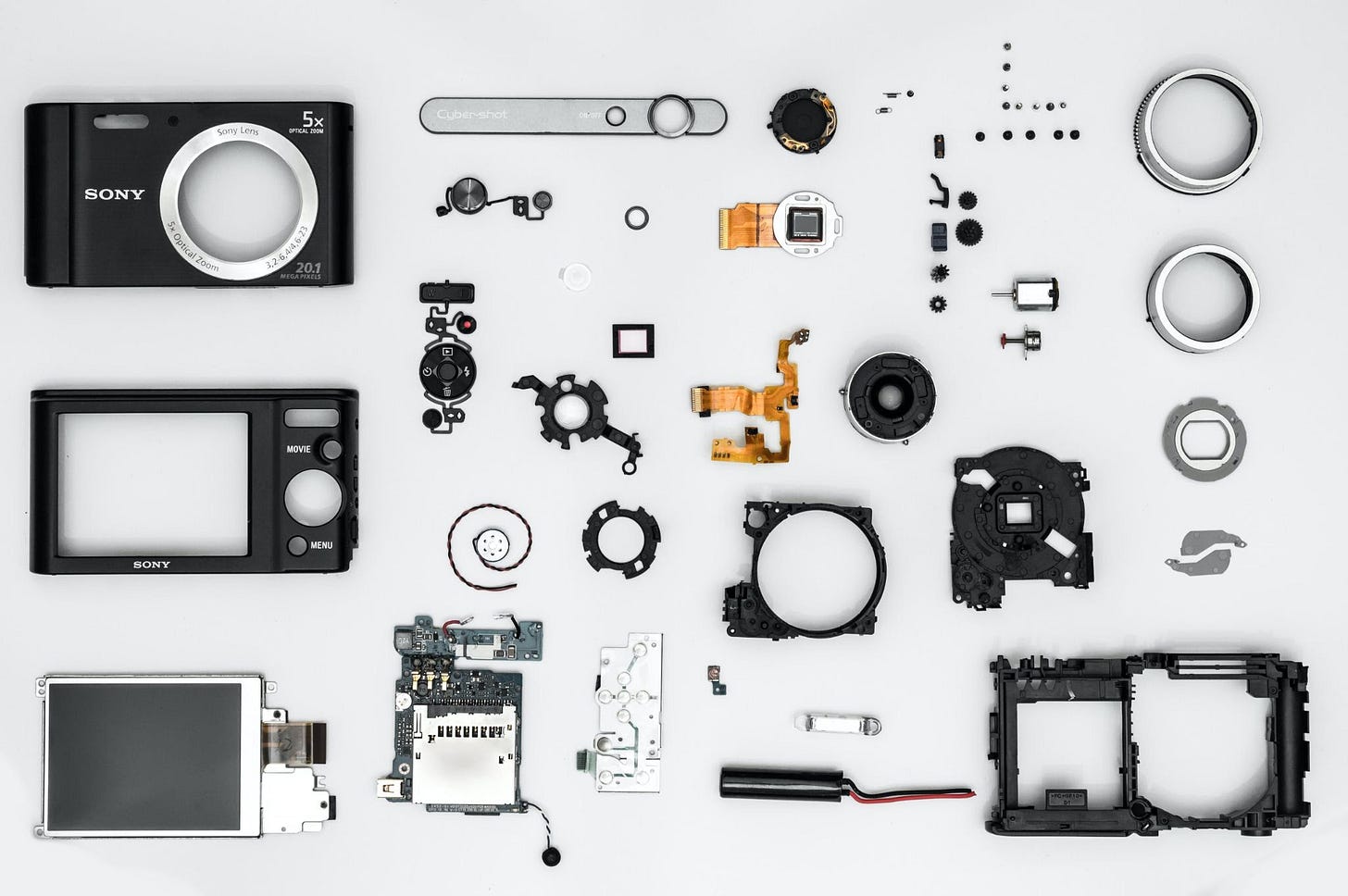

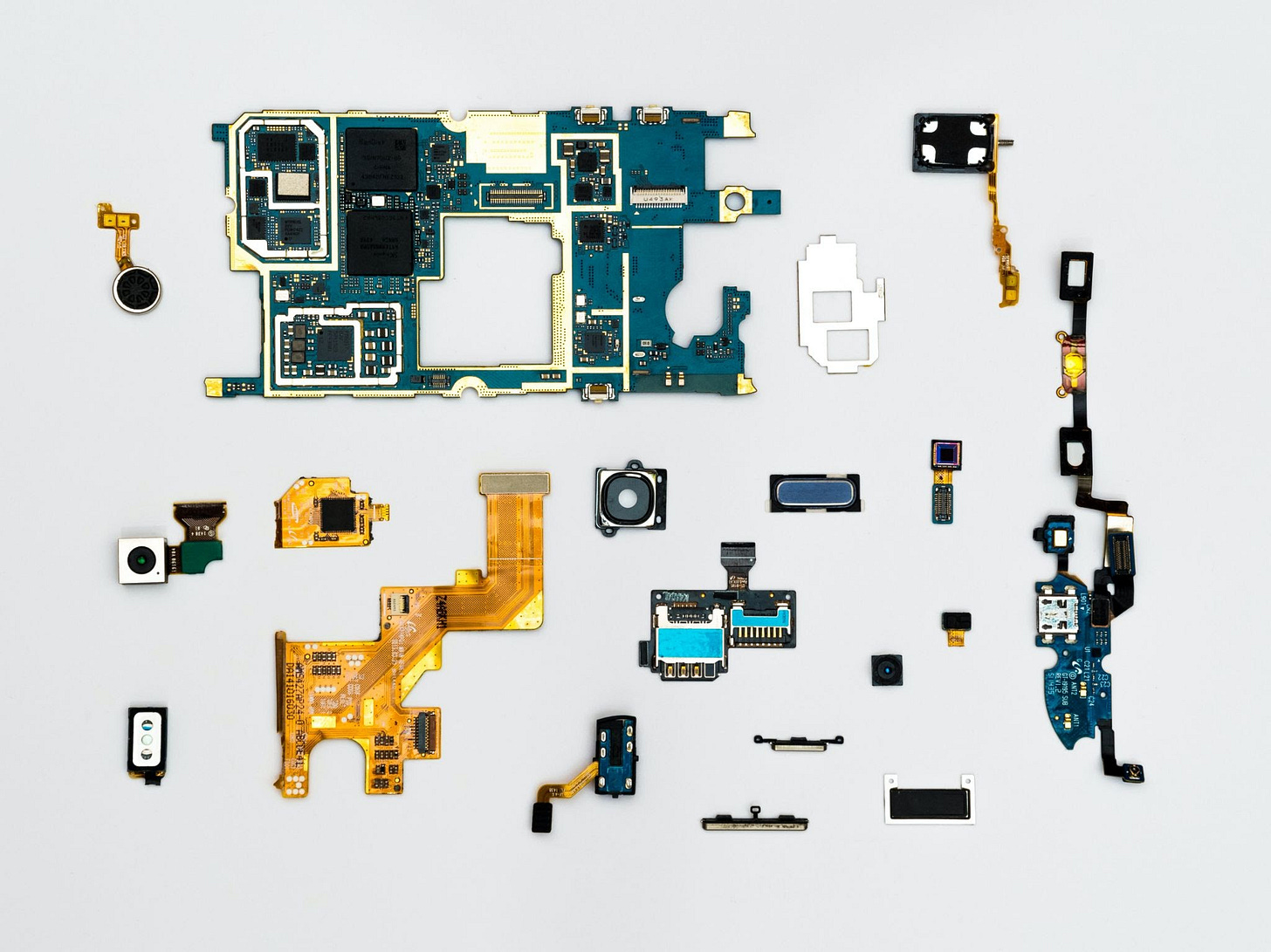

When Jamie passed away, we had a book displayed on our coffee table called Things Come Apart. It’s a beautiful book, full of photographs of objects disassembled. It was a Christmas gift from my brother, given to Jamie six weeks before he died.

For the longest time, that book, once an innocuous gift, felt like a cruel joke. I kept it on our coffee table for months, not wanting to move anything in our house for fear of losing yet another connection with Jamie. Eventually, though, I stashed it out of sight. Those disassembled objects reminded me of how everything came crashing down when Jamie collapsed. But unlike those dismantled cameras, computers, and appliances, Jamie’s life—the life we shared—couldn’t be put back together.

I never got rid of that coffee table book. Even as I pared down my belongings for our move to Atlanta, I kept it. But it was only until now, as I wrote this essay, that I revisited those photographs.

There are a handful of essays interspersed throughout Things Come Apart. One of them is written by Kyle Weins, the co-founder and CEO of iFixit, an open-source online repair community. In his essay, Weins writes about the fact that, as a society, we are often too quick to replace a broken object than to try to repair it.

“Life without conflict is a fraud,” Weins wrote. “We all have to fight entropy, and refusing to engage in that battle is to ignore what makes us human. Every time you fix something that entropy has broken, you claim a small victory.”

Some things, like death, are unfixable. But as long as we are alive, we have the ability to rise up to the challenges that face us. It’s up to us to decide whether we’re willing to meet them.

When I started writing today’s newsletter, I was in a terrible mood. I didn’t know what I was going to say. I felt disheartened, frustrated by all of the bad news in the world and plagued by the dark cloud perched in my brain.

But as I started to write—as I began to pull all of those stormy feelings apart—everything felt a bit more manageable. I was feeling bad about specific issues: a lack of sleep, a rush of premenstrual hormones, a hesitation to face some past traumas in therapy. As I named these things, I was able to remind myself that everything I was experiencing was temporary.

This is a phase.

Those bigger crises fit into the picture, too. My mind is especially heavy with fears of climate change and of COVID. These are things that will not quickly go away, that we will contend with for an unpredictable amount of time. Still, naming those fears helped.

When you see all of the pieces of a disassembled object in a pile, it looks like chaos. It’s overwhelming to even think about where to begin in putting it back together. But if you separate and label the parts, it’s not as daunting. You’ve already begun the process of moving ahead.

“To live well is to press forward,” wrote Weins. “Seeking out new challenges and opportunities fulfills us and makes us into better people. Every challenge that we overcome grants us greater perspective and prepares us for the next challenge. The solutions we craft become part of us, making us better as we improve the world around us.”

I don’t know what motivated me to hold onto that book, but I’m glad I did.

xoxo

KHG

p.s. What’s one small thing that has you feeling a little better about the state of the world? It could be something small in your personal life or a larger example from your wider community. Pick one thing, and tell me about it by replying to this email, leaving a comment, or sending me a message. I’ll compile everyone’s hopeful examples in Friday’s newsletter, which is for paying subscribers.

I can’t wait to read what you share. Together, maybe we can create one giant reason to look forward to the future.

💖 Sharing is caring

Slow your scroll! Thank you to Alyssa for this lovely and generous shoutout. Many of you shared last week’s post, and it meant so much to me. Such a great way to return to newsletter-writing land.

As always, please consider sharing My Sweet Dumb Brain on social media, recommending it to a friend, or—if you haven’t yet—becoming a paid subscriber.

My Sweet Dumb Brain is written by Katie Hawkins-Gaar. It’s edited by Rebecca Coates, whose small bit of happiness right now is listening to Glennon Doyle’s podcast, We Can Do Hard Things, and talking about it with her pod-squad (shoutout to Hayley and KHG!) Photos by Dan-Cristian Pădureț on Unsplash.

This newsletter contains Bookshop.org affiliate links.

Katie I just read this. I love your brutal honesty. And as I just shared with Billy & Friends, I just fixed our washing machine which had a broken drain pump. We need the washing machine. It's important. We have 9 guinea pigs who need to have their bedding washed on an ever so regular basis. And I did it, with help from our lord and savior, YouTube.

And you know what, I'm in a great mood. I think I may have gotten a serotonin + endorphin boost by doing something new, risky, and exciting.

I'm encouraged that our schools are open this September and children are returning to some 'normalcy'. This gives me hope that our world is hopefully on it's way to finding a new normal.